Exctract from a lecture at the Japanese swordfighting summerschool in Velling, Denmark, 1 July:

Exctract from a lecture at the Japanese swordfighting summerschool in Velling, Denmark, 1 July:

1.

An important part of national cultural identities are the myths and folklore that shape, often at an unconscious level, our understanding of ourselves and our origins and communities. It is extremely interesting that these myths and this folklore have specific local forms and variations, but are nonetheless often obvious embodiments of more general myths or, if you wish, archetypes that can be found throughout many different cultures and nationalities. In this lecture I would like to discuss with you one of the most famous of these myths, a myth that is built upon actual historical events and social experiences: the myth of the Noble Robber, whose archetype is Robin Hood.

For those of you who know me only as a martial arts practitioner, some explanation may be needed why I have chosen Robin Hood as the theme for my lecture at this summer school. Apart from the obvious connection of the noble robber with the handling of violence and with weapon arts, there are direct historical links between outlawry and Eastern martial arts. At first sight this might appear to be strange, since the Eastern and especially the Japanese martial arts have been integrated into a culture in which authority, obedience to the law and to one’s lord, emperor or country, and subjection of the individual to the community are the highest values. But as always, Chinese and Japanese cultures have an undercurrent that is opposed to the dominant values, a yang to the dominant yin of obedience. The archetypal Robin Hoods of Chinese and Japanese culture are the so-called Outlaws of the Marsh, or the bandits of Liang Shan Po. The 14th-century Chinese novel Shui Hu Zhuan (literally The Marsh Chronicles), based on historical events, tells us the story of a ‘hundred some-odd men and women banded together on a marsh-girt mountain (and) became leaders of an outlaw army of thousands and fought brave and resourceful battles against pompous, heartless tyrants.’

Here is one of them: ‘Nine-Dragons Shi-Jin’, in a famous woodblock print by the 19th-century Japanese artist Kuniyoshi Utagawa. It shows how the Outlaws of the Marsh also captivated the Japanese. And in fact, outlaws, masterless warriors, bandits, and gamblers (ronin or roshi) have played an important and extremely interesting role in the development of Japanese swordsmanship and martial arts.

In my other persona, as a historian, I have always been interested in how actual historical figures, such as the piratical incarnations of our noble robbers, lived and were transform and eulogized as well as demonized in the popular imagination.

All these points will return in this lecture, but let us start with the greatest and most famous of them all: Robin Hood.

2.

Lythe and listin, gentilmen,

That be of freborne blode:

I shall you tel of a gode yeman.

His name was Robyn Hode

Robyn was a prude outlaw,

Whyles he walked on grounde:

So curteyse an outlaw as he was one

Was nevere non founde.

(R B Dobson & J Taylor, Rymes of Robyn Hood: An Introduction to the English Outlaw (London: Heinemann, 1976) 79)

The Gest of Robyn Hode is the most elaborate ballad of Robin Hood in existence and has been described by the English historian Gillian Spraggs as an ‘outlaw romance’. We can note that it appears at roughly the same time as the Outlaws of the Marsh, and there are many similarities between men as Nine-Dragons Master Shi and Robin Hood. They are both accomplished martial artists. They are honourable men, having aristocratic virtues as generosity and courtesy towards women. Their enemies are evil lower magistrates like the Sheriff of Nottingham, not the King or the Emperor. And although they have aristocratic virtues, they are not aristocrats themselves. Their basis of operations is in wild territories, outside the powers of the rulers-that-be: the marshes of Sung dynasty China, and the green woods of Plantagenet England. There has been much discussions about whether Robin Hood is the champion of the people, in this case the peasants of medieval England, but the gest of Robyn Hode clearly defines him in the third line as a ‘yeoman’. A yeoman is neither a nobleman nor a serf. Originally, he was a low-ranking member of a nobleman’s household – freeborn and honourable, often skilled as foresters and huntsmen, which is why Robin Head wears the well-known green outfit and is carrying bow and arrows. By the late middle ages, free landholders and artisans also came to be designated as and equivalent in law to yeomen. Robin Hood is a hero of this class, although he also becomes a hero for the nobility itself. To begin with, role-playing games happened in late medieval England at lower levels of the social scale: summer festivities where young men dressed in green, had archery contests and went around ‘gathering for Robin Hood’. Later this moves as a kind of ‘outlaw chic’ to the higher levels of society. By the early 1500s, king Henry VIII and his friends will disguise themselves as Robin Hood and his merry band and do a mock attack on their lady friends at the court.

Already by then Robin Hood was more a figure of myth and fantasy then of reality, and what cultural historians call a ‘cultural script’ was written that defined the behaviour that should go along with playing the role. People, from high to low, enjoyed acting out the more playful aspects of this fantasy in. But we will see later that the more realistic and violent aspects of this script would also be played out, up to this very day.

3.

These role-playing games were and still are fantasies, but they had actual roles in the functioning of the social fabric and in daily life. The role-playing phantasy made a short escape possible from the demands of everyday reality, either passively (by listening to, looking at, and reading of the image of Robin Hood), or even actively, by strutting around dressed in green and pretending to be a happy outlaw. I think it is very interesting that this phantasy was grafted upon the acts of and memories of a very real historical figure, or even figures. As Spraggs write, ‘There is evidence, sketchy but very suggestive, that as early as the thirteenth century names such as ‘Robehod’ or ‘Robynhod’ had become nicknames used by or applied to particular individuals, some of whom, at any rate, were noteworthy for typical Robin Hood activities, such as robbery, archery or poaching.’ [p. 56]

Historian David Crook has unearthed a reference to Robin Hood as far back as an exchequer memoranda roll of 1262. This is about a process against the prior if Sandleford, who had seized the cattle of a person who had fled from accusations of larceny and harbouring). The prior had kept the proceeds from the cattle for himself, instead of turning them over to the king. The clerk at the chancery who recorded the proceedings allowed himself a little joke. Though the name of the person who had fled was William, son of Robert Smith (Le Fevre), he turned it into William Robehod. ‘It is to be supposed that the man who altered the name thought of Robin Hood as a criminal and fugitive.’ And indeed, one Robert Hod from Yorkshire fled the jurisdiction of the king and his chattels were taken in July 1225. We don’t know what he exactly did, but here we may have the original Robin Hood.

And David Crook has gone even further in his speculations. In that same year 1225 king Henry III ordered the sheriff of Yorkshire to hire sergeants and to seek, take and behead one ‘’Robert of Wetherby, outlaw and evildoer of our land.’ One of the expenses the sheriff later claimed was ‘for a chain to hang Robert of Wetherby’ – to hang him and to put him on display for the public? Was Robert of Wetherby the same man as Robin Hod? In historical England, Robin was captured and hung by the chain. In the plays and stories about him, he would outwit the sheriff. (David Crook, ‘The Sheriff of Nottingham and Robin Hood: The Genesis of a Legend?’, in P.R. Cross and S.D. Lloyd, eds., Thirteenth Century England, Vol. II (Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 1988, 59-68)

After 1225 the name Robin Hood keeps popping up to name real bandits. A petition to parliament mentioned one Piers Venables of Derbyshire, who had rescued a prisoner on his way to Tyburn castle, and who had a band of followers ‘beying of his clothinge, and in manere of insurrection went into the wodes in that country like it hadde be Robyn Hode and his meynes.’ Criminals even started to call themselves Robin Hood, like one Robert Marshall of Wednesbury who was accused in 1497 to have led a group of more than one hundred in a riotous assembly at Willenhall. One of those ‘criminals’ who were called Robin Hood have become famous again: remember Guy Fawkes? [Dobson & Tyler, 4] We will have occasion to return to him.

4.

Robin Hood, then, is a complex figure, mixing historical reality, myth and phantasy. Marxist historian E.J. Hobsbawm in a booklet first published in 1969 has therefore relegated him to the figure of an archetype. Hobsbawm was and is a classical Marxist, who believed that peasant revolutionaries and rebels were reactionary and doomed to a lost fight against the march of history and the rise of capitalism. One of the forms their rebellion took was that of ‘social bandits’: social bandits, in his view, were universally found in human societies. Relatively recent examples of these bandits are Jesse James, murdered in 1882, who was reputed never to have robbed an ex-Confederate; even more recently the Brazilian bandit Lampiao or Lampeao (1898-1938), and the Sicilian Salvatore Giuliano (1922-1950). What characterized these ‘social bandits’, according to Hobsbawm, was their relationship to their own social class, the peasant. In mythology, though not always in actuality, they would rob the rich and give to the poor. Despite regional variations, their presence was universal. Hobsbawm devised a typology of these social bandits (‘noble robbers’, ‘avengers’, and ‘haiduks’ – the latter are the robbers of Southeastern Europe, akin to the outlaws of the marsh) and relegated Robin Hood to the archetype of the Noble Robber. Despite his Marxism, and though his book concerned itself mainly with bandits in actual history, Hobsbawm was quite sympathetic to the image or symbol of the robber. I quote: ‘… there is more to the literary or popular cultural image of the bandit than the documentation of contemporary life in backward societies, the longing for lost innocence and adventure in advanced ones. There is (…) a permanent emotion and a permanent role. There is freedom, heroism, and the dream of justice.’ (p. 131-132).

Historical studies as that of Hobsbawm are eager to separate fact from myth, but one of the interesting things is how difficult this is: partly because already at a very early stage the role of noble robber, as I said before, becomes a cultural script, available to everyone with the nerve and dash to act it out. This already starts quite early in medieval times, as we have seen. The key slogan for this script became: take from the rich and give to the poor, something instantly recognizable by all people who find themselves poor and have a grudge at what they see as the undeserved and anti-social wealth of the rich. There is hardly ANY evidence that the real Robin Hoods of the 13th century did give their booty to the poor. Their attitude may more have been such as ironically depicted in the 1969 comic book Jesse James, a volume in the famous Lucky Luke series. This is an excellent though simplified example of how a cultural script works: Jesse becomes a bandit inspired by a book on Robin Hood, but then decides to keep the booty he takes from the rich in his own (poor) family.

We do not know if real Robin Hoods didn’t operate from the same mind-set as Rene Goscinny’s Jesse James. We do know however that the idea of take from the rich, to give to the poor, is evident in popular festivities in 15th-century England. I quote Spraggs: ‘It is likely that much of the performance [of early Robin Hood plays] would have been improvised extempore, as the young men of the parish engaged in archery contests or went ‘gathering’ – collecting money among the crowd who turned out to see the fun. This would have allowed for plenty of appropriate role-playing, since, after all, relieving passers-by of their spare cash was one of the things for which Robin Hood’s band was famous’. We have here a kind of ‘creation of situations’ or happenings in which young people acted out their fantasies of Robin Hood and the free and wild outlaw life in a more or less structured environment, a parallel in daylight to the wild nightly revels of the Walpurgis night. This, of course, was not to everybody’s liking. ‘… a disapproving commentator in Elizabeth’s reign [note, we are now in the second half of the 16th century] complained that those who refused to pay up on these occasions could expect to be ‘mocked and flouted at shamefully’, and he says that in extreme cases they might even be ducked in water or ‘carried upon a Cowlstaffe’ – set astride a pole and carried about to be jeered at.’ But it is unlikely that such rough treatment was typical. As a general rule, the ‘gatherings’ took place under very respectable auspices: they were organised, or at least countenanced, by the churchwardens, and the money that was collected was handed over to them. Some of it would be spent on a feast for the men who had played the parts of Robin Hood and his company, and the rest would be put towards the expenses of the parish. This may offer another clue to the beginnings of the notion that Robin Hood ‘took from the riche and gave to the poor’, since it was common for the parish authorities to pay out sums in charity to people who were in need.’ [Spraggs, 53-54]

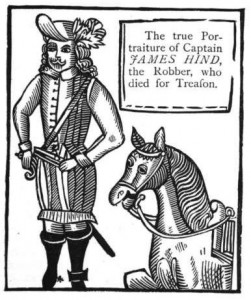

Goscinny’s example may be a caricature, the cultural script of Robin Hood was available to robbers in England. I give one example: a 17th-century highwayman who consciously tried to portray himself as a noble robber in the tradition of Robin Hood. James Hind (1616-1652) was arrested in London in November 1651, after his denunciation by a comrade soldier from the army of Charles II. Two months before the forces of Oliver Cromwell had defeated the royalist troops. Charles had to make a sensational escape to the continent and it was rumoured that Hind had assisted him and even engineered the escape. But he was also known in another capacity: as a robber on the highways.

Hind was tried in March 1652 and claimed benefit of clergy. Unfortunately it turned out he could not read aloud the text he was given, so proving his claim. Still, he seemed to escape his sentence, because in the aftermath of the Civil War Parliament had passed an act of general pardon. But Hind’s luck did not hold, since he now was tried on the charge of treason, a charge for which the act did not apply. He was convicted and, in November 1652, hang, drawn and quartered.

While in prison Hind discussed his exploits with one or more hack-writers, who brought out two pamphlets: Hind’s Ramble, and Hind’s Exploits. These made him the most famous robber of his day, but also show how carefully Hind tried to live up to a reputation as a genuine Robin Hood. He was depicted as a sympathetic robber, who carried out his robberies with style (Grace), and who had courage, presence of mind, ingenuity and a prankish wit. In another pamphlet he was reported to have said:

‘I owe a debt of God (…) that he hath kept me from shedding of blood unjustly (…) Neither did I wrong any poor man worth of a penny, but I must confess, I have (…) made bold with a rich Bompkin, or a lying Lawyer, whose full-fled fees from the rich Farmer, doth too too much impoverish the poor cottage-keeper.’ [Spraggs 164]

Was this a true statement? We do not know, but that is not the point here. The point is that he wished to present this image to the public. In a similar vein, an eighteenth-century robber once declared explicitly that he robbed the rich to give to the poor. And this would not just be an image for the public. Significantly, the former highwayman and medical doctor James Clavell tells us in his 1634 memoirs that his fellow robbers would whistle the tune of a Robin Hood ballad as a signal to mount an attack.

5.

The archetype of Robin Hood is typically English, but both myth and reality show themes that are obviously themes in other cultures as well. The noble robber becomes an outlaw and breaks the law. To many, he is no more than a bandit, who out of greed and anti-social impulses takes what is not his, if necessary by violence. But to others, and this is not necessarily limited to the poor, he is a hero: he breaks the law, that is true, but only because the law is the law of the rich and powerful, and often unjust. He (and occasionally she) dares what other men and women do not, but deep in their heart would crave to do: out of lust for adventure, out of hatred to the rich, out of a feeling of justice. In short, the noble robber is an ambivalent figure, both in myth and in reality. But his ambivalences transcend local, Yorskhire or English culture: they are presented wherever people feel oppressed or cramped.

We should find the Noble Robber therefore where we are now. I hardly can read any Danish and am not particularly familiar with Danish history, and could not find much literature on the Danish situation in languages I do read. So I asked my friends here to come up with Danish examples of Robin Hood, and they came up with Jens Langkniv {Longknive|, Jens Olesen, and what I can gather in him all ambivalences of the Noble Robber are present. Was he a bandit, or a hero?

6.

I was also given another Danish example, and I think he is even more complicated because he is not so much an individual robber as one who leads collective action against the powers-that-be.

‘In the northernmost part of Jutland, in the region known as Vendsyssel, the rebellion took a particularly disturbing turn [by the summer of 1534]. Egged on by one ‘Skipper Clement’, a privateer in Christian II’s service, peasants and townspeople in Vendyssel took up the case of the captive king [Christian II], seizing Alborg and defeating a noble levy at Svenstrup in October. The intended target of Skipper Clement’s mob was not so much the pretender from Holstein [Christian III] as it was the nobility in general and consequently the Vendsyssel rebels engaged in an orgy of class-based violence, burning noble manors and hunting down local magnates.’ [Paul Douglas Lockhart, Denmark, 1513-1660: The Rise and Decline of a Renaissance Monarchy, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 27]

Is Skipper Clemens an example of medieval and early modern revolutionaries who by violent action wish to topple down existing structures and create a heaven on earth? There are many of them around in the 16th and 17th centuries: in the German Peasant Revolt, in the Anabaptists at Munster, in the attempt of Anabaptists to take over the city of Amsterdam in 1535 etc. The privateer Skipper Clemens is Robin Hood turned revolutionary. And here he points forward to another powerful strain in the Robin Hood tradition.

7.

The French revolution and the Romantic Movement gave new impetus to the image of Robin Hood as not only a noble, but a revolutionary robber. In 1795 the English lawyer and antiquarian Joseph Ritson (1752-1803) published a collection of poems, songs and ballads of Robin Hood. Ritson was a republican and a vegetarian, who hated the reigning royal family. Contemporaries attributed this to his ‘incipient insanity’: Ritson was removed to the lunatic asylum of Hoxton and died there after a few days. In his introduction to his Robin Hood collection he portrays Robin as a noble robber, taking from the rich and giving to the poor, only killing in self-defence and gallant to women. But Ritson goes even further and enlists Robin in the course of his own republicanism and anticlericalism:

‘Our hero, indeed, seems to have held bishops, abbots, priests and monks, – in a word, all the clergy, regular and secular, – in decided aversion […] the pride, avarice, uncharitableness, and hypocrisy, of these clerical drones, or pious locusts, will afford him ample justification […]

[He} for a long series of years, maintained as sort of independent sovereignty, and set kings, judges, and magistrates at defiance […[

[He was] a man who, in a barbarous age, and under a complicated tyranny, displayed a spirit of freedom and independence, which has endeared him to the common people, whose cause he maintained, (for all opposition to tyranny is the cause of the people)…’

The revolutionary outlaw became a staple-place of Romantic literature, who gave him a tormented and dark twist, as in Schiller’s Robber or in Byron’s Corsair. And this dark twist remains when we jump from the Romantic era to that of our own, and look at an omnipresent and transcultural image of the noble robber as revolutionary.

The images for this revolutionary Robin Hood can come from all kinds of unlikely sources. Here is one that is around right here, at the present moment, visible in any social protest around the globe:

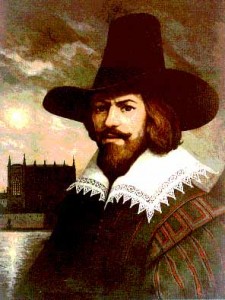

Guy Fawkes (1570-1606), one of the instigators of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 (an attempt to blow up the Houses of Parliament) was himself from Yorkshire, as was Robin Hood. James Sharpe in his study of Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot (Remember, remember, the Fifth of November, 2005), has unearthed popular rhymes on Fawkes. Most of it is quite negative, for instance:

Remember, remember the fifth of November

Gunpowder, treason and plot.

I see no reason, why gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot.

Remember, remember, the fifth of November,

Gunpowder, treason and plot!

A stick or a stake for King James’ sake

Will you please to give us a fagot

If you can’t give us one, we’ll take two;

The better for us and the worse for you!

Or:

Guy, guy, guy

Poke him in the eye,

Put him on the bonfire,

And there let him die

But see this interesting rhyme:

Here comes three jolly rovers, all in one row.

We’re coming a cob-coiling for t’ Bon Fire Plot.

Bon Fire Plot from morning till night !

If you’ll give us owt, we’ll steal nowt, but bid you goodnight.

Fol-a-dee, fol-a-die, fol-a-diddle-die-do-dum !

The V for Vendetta movie, the 2005 adaptation of a 1980’s comic book series written by Alan Moore, is an excellent example of the re-circulation of the Robin Hood image in an unexpected form (in contrast to the stereotyping of most actual Robin Hood movies), and shows how symbols are taken up in a worldwide culture. And we also get back again to one of my own basic fascinations for Robin Hood. Because the Guy Fawkes of V for Vendetta is a consummate martial artists and swordfighter.