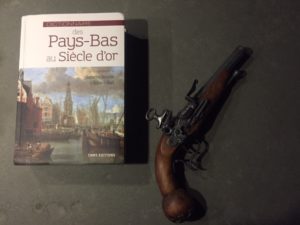

I had great pleasure in contributing the entry on ‘corsairs, piraterie’ to this magnificent new, French-language dictionary of the Golden Age Netherlands, published by the Centre national de la recherche scientifique in Paris.

I had great pleasure in contributing the entry on ‘corsairs, piraterie’ to this magnificent new, French-language dictionary of the Golden Age Netherlands, published by the Centre national de la recherche scientifique in Paris.

Onlangs adviseerde het Huisartsengenootschap tegen de medische verstrekking van cannabis vanwege het ontbreken van overtuigend wetenschappelijk bewijs voor de werkzaamheid. Dat neemt niet weg dat alleen al in Nederland tienduizenden gebruikers in verschillende vormen cannabis gebruiken als zelfmedicatie. Ze hebben veel meer ervaringen met de werking op henzelf dan hun zorgverleners. Ze zulllen er ook niet mee ophouden, wat de uitkomst ook zal zijn van het legaliseringsdebat.

Onlangs adviseerde het Huisartsengenootschap tegen de medische verstrekking van cannabis vanwege het ontbreken van overtuigend wetenschappelijk bewijs voor de werkzaamheid. Dat neemt niet weg dat alleen al in Nederland tienduizenden gebruikers in verschillende vormen cannabis gebruiken als zelfmedicatie. Ze hebben veel meer ervaringen met de werking op henzelf dan hun zorgverleners. Ze zulllen er ook niet mee ophouden, wat de uitkomst ook zal zijn van het legaliseringsdebat.

Opmerkelijk is dat er grote overlappingen bestaan tussen dit ‘lekengebruik’ van cannabis en het medische gebruik van cannabis in de geschiedenis. Cannabistincturen duiken al tenminste drie eeuwen geleden op in de Nederlandse farmaceutische handboeken. Tot het verbod van het gebruik van cannabis in de wijziging van de Opiumwet in 1953 staan ze erin. Historici als ikzelf hebben uitgebreid materiaal over het gebruiken en voorschrijven van cannabis in het verleden gevonden.

Medisch Contact publiceert deze week een bijdrage van onze onderzoeksgroep medicinale cannabis aan de Universiteit Utrecht, een multidisciplinair team van onderzoekers, waarin we aandacht vragen voor het serieus nemen van deze historische en lekenkennis.

Gottfried Wilhelm Schilling wrote an influential treatise on leprosy in 18th-century Dutch controlled colonial Suriname.

In my book on Leprosy and Colonialism I have written more in detail about this adventurer/surgeon/physician, who became a slave doctor in the colony and framed a racialized and sexualized pathology of leprosy. Schilling’s treatise is an example of how the fears of the white colonizers for the black slaves permeated medical colonial thought and policies, leading to compulsory segregation of leprosy sufferers.

There was some confusion of Schilling with another person of the same name, living in Suriname at the same time. Thanks to the work of American historian Nathalie Zemon Davis and of Philip Dikland of the Suriname Heritage Guide database we now know that there were two Schillings and that the slave doctor was born in Germany (Brandenburg), becoming one of the many German employees of the Dutch trading companies and colonial regimes. Nathalie Davis will shortly publish more on the subject.

My book on 200 year history of leprosy in a colonial society (Dutch Suriname) has finally been published .

.

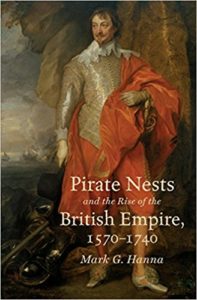

In Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire, 1570-1740 (published by University of North Carolina Press in 2015),  American historian Mark G. Hanna questions the popular image of the pirate of the 16-18th centuries as a rebel against society and as a social bandit. Hanna shows how in the Anglophone world of England and its North American and Caribbean colonies piracy was a possible and not unusual career move of seamen. In the course of the 17th century merchants and sea captains in many English colonies, especially those that were ruled by charters (for example Rhode Island) were heavily involved in piracy. This was moreover an economic necessity for these colonies, since it was the only way to ensure import of bullion and goods such as textiles. Piracy was necessary for the rise of the British Empire, so Hanna claims. It took until the early 18th century for a decisive change: trade became more important than plunder as a source of income for the colonies, powerful players such as the East India Company resented the adverse effects on global trade of raids on ships from India, and the state and colonial governments turned piracy into an activity of outlaws.

American historian Mark G. Hanna questions the popular image of the pirate of the 16-18th centuries as a rebel against society and as a social bandit. Hanna shows how in the Anglophone world of England and its North American and Caribbean colonies piracy was a possible and not unusual career move of seamen. In the course of the 17th century merchants and sea captains in many English colonies, especially those that were ruled by charters (for example Rhode Island) were heavily involved in piracy. This was moreover an economic necessity for these colonies, since it was the only way to ensure import of bullion and goods such as textiles. Piracy was necessary for the rise of the British Empire, so Hanna claims. It took until the early 18th century for a decisive change: trade became more important than plunder as a source of income for the colonies, powerful players such as the East India Company resented the adverse effects on global trade of raids on ships from India, and the state and colonial governments turned piracy into an activity of outlaws.

Hanna gives an interesting and detailed description and analysis of these developments. In doing so, he clearly relishes the idea of turning over our image of the pirate as rebel. He also questions the democratic character of the Golden Age pirates, the ones who did become outlaws. For instance, the articles of agreement that these pirates signed, usually seen as evidence of democracy, were according to Hanna meant by the captains to ensure that crewmembers could not go back to the world of legality. After all, their signatures were written evidence that made the pirates run the risk of hanging. Hanna also questions whether the presentation in the famous chapter on Captain Misson in Johnson’s General History … of The Most Notorious Pirates, of a democratic and egalitarian pirate society on Madagascar, was meant as an utopian fantasy; rather, he sees this description as dystopian, since it confirmed all the fears and prejudices of contemporaries.

However, proving that piracy was an integral part of colonial expansion and society up until the early 1700s is not the same as disproving that piracy could be an act of social rebellion. It all depends I presume on one’s views on what (social) politics is. I have argued in The Devil’s Anarchy that the social rebellion of pirates took place on the level of the rhythms of everyday life, rather than on the level of consciously creating a new society. Even when outlawed, pirates needed connections to the legal economy, if only to sell their booty, to rest, and to re-outfit. This was true for early 17th-century pirates in European waters such as Simon the Dancer and Claes Compaen, for the buccaneers and flibustiers of the Brotherhood of the Coast, as well as for the Golden Age classical pirates. That increased importance of regular trade (that had to be safe-guarded from pirates) went hand in hand with a process of state building and the ‘extraterritorialization of violence’, turning pirates into outlaws (a process already described by Janice Thomson in her 1994 volume Mercenaries, pirates, and sovereigns) did not change this fact of everyday pirate life.

Pirates and other criminals needed and need middlemen, financiers, and buyers in the legal world. Hanna makes a significant contribution in detailing how in the 16th-18th centuries this also worked the other way around: the legal economies needed the illegal to survive and to embark on a process of ‘piratical colonization’. Only when expansion of trade and empire building did no longer need the pirates did the sea rovers turn into the ‘enemies of all mankind’.

Op de website van IsGeschiedenis is een artikel van mij over LSD en XTC in de westerse maatschappij opnieuw gepubliceerd.

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

In this chapter the ‘adventurer-scientist’ is introduced. The chapter starts with German natural scientist Georg Marcgraf, finding himself in 1638 among the ‘cannibalistic’ Tapuya Indians of Brazil. At the siege of Portuguese-held Bahia the Dutch soldiers are plagued by diarrhea and dysenteria. Marcgraf discovers treatment methods among the Brazil Indians.

In the 17th and 18th centuries the European newcomers to the tropics had to deal with the disease-environment and had to find ways of survival: methods of prevention, hygiene and treatment. Finding this knowledge needed a special kind of researcher: the adventurer-scientist with a freebooter spirit. The adventurers were a very diverse group, but they shared some common characteristics. To start with they had a capacity for accurate and detailed empirical observations and for description of these observations. They were part of a network for the dissemination of information. Their activities had important practical and pragmatic components stimulating trade, expansion, and even privateering and piracy. An adventurer-scientist was able to open-mindedly create and sustain contacts with indigenous and to him strange cultures. He possessed personal characteristics such as perseverance, a healthy constitution, and ruthlessness, and he could operate in a violent environment. And he was able to operate autonomously. In fact, when substituting the words ‘searching for knowledge’ with ‘searching for Spanish treasure’, the characteristics do not change much.

The adventurer-scientists encountered a world in which the disease-environment was radically changing: the world of the ‘Columbian exchange’ of diseases and the spread of new health problems from Africa as a consequence of the slave trade. The next chapters will investigate their adventurers and significance in the world of the tropical Dutch Atlantic: West Africa, Brazil and the Caribbean.

Chapter 2

A MOTHER OF PUTREFACTION’ – CONFRONTING THE TROPICAL CLIMATE

Here the health problems of the Europeans in the tropics are discussed. At first sight the tropics, in West Africa or the Caribbean, look like paradise. But soon the snakes are discovered: the murderous heat, the unhealthy air, ‘hot fevers’, the ‘flux’ (diarrhea) and bloody flux (dysenteria), scurvy, sexually transmitted diseases because of intercourse with black women, parasites, worms and insects. Description of the African Gold Coast as the ‘white man’s grave.’ Health problems affected most in particular common soldiers and servants because of their housing conditions and mal-nutritious diet.

Chapter 3

SURGEONS OVERSEAS

This chapter introduces the doctors, surgeons and barbers who went on voyages and overseas to the tropics. It discusses their social origins, their (lack of) training and qualifications and the development of textbooks based on experiences overseas. The level of competence of the surgeons fluctuated widely and there was sometimes considerable mistrust towards them. The case is discussed of a surgeon in the Dutch navy: he was executed after having confessed to a pact with the Devil and to the murder of his patients.

Chapter 4

PIRACY OF KNOWLEDGE

In this chapter problems of health and disease are pictured from the perspective of the European adventurers: how did they experience their problems? Early modern medical thought and practices are evaluated as a kind of common sense medicine, centered not on pathogens and specific diseases but on disturbance of balance and with a strong holistic emphasis, placing the individual in an environmental context. In this framework, health problems are specific to certain regions and if there are health problems in a region, there are bound to be solutions there as well: specific prevention and treatment methods. Operating in this framework stimulated an open-minded view of health practices of other nations and cultures.

The first way to obtain medical knowledge in the tropics was a ‘piracy of knowledge’: this included a literal spying on practices of the enemies of the Dutch, the Spanish and the Portuguese. Dutch merchants at the end of the 16th century, working in the service of the Spanish and the Portuguese, returned to the Dutch Republic with knowledge on islands and inlet harbors in the Atlantic and the Pacific, There fresh supplies could be obtained, including lemons and oranges against scurvy, and patients could be rested and recover.

Spying discovered the uses of local medicinal plants in West Africa and South America. Knowledge was also obtained from indigenous inhabitants: e.g., South American Indians taught methods to safely extricate worms from the body.

Chapters 5

ADVENTURERS AND INDIANS IN BRAZIL

Between 1630 and 1654 the Dutch occupied the Portuguese colonies in Northeast Brazil and fought a protracted guerrilla war against their enemies. They found allies among the Brazil Indians, especially the sedentary Tupi and the nomadic Tapuya. In particular the Tapuya proved to be fierce warriors. But the Dutch were ambiguous about their allies. On the one hand, the Tapuya were seen as living in an anarchist and egalitarian paradise, without trade, government, and property. On the other hand, they were seen as lazy, cruel, and as followers of the Devil.

From a medical point of view the Indians were considered to be superbly adapted to the tropical environment. Being close to nature, they learned about the medicinal properties of plants from animals. It was thought therefore that the Dutch could learn about these properties and about suitable medical practices from the Indians. A few adventurers like Georg Marcgaf and the poet, soldier and treasure-hunter Elias Herckmans went on expeditions into the interior and learned from the Indians. The German Jacob Rabe went further: he took a Tapuya wife, lived among the Indians, and joined them in attacks on Portuguese settlers. He was finally murdered on instigation of a Dutch officer who disliked his close association with the Tapuya.

The knowledge obtained by the adventurers in the Brazil contact zone with the Indians found its way into medical practice and treatises, as is testified by he Historia naturalis Barsiliae (Natural History of Brazil, 1648), celebrated as the first text book on tropical medicine.

Chapter 6

ILLNESS AND DEATH ON THE SLAVE SHIPS

The slave trade profoundly affected the social, political and biological environment of the Caribbean. Between 1660 and the Napoleonic era Dutch trading companies were key players in the slave trade with West Africa. Centered on the slave markets on the Caribbean islands of Curacao and Saint Eustatius, and the markets and plantations of Suriname and Guiana on the South American continent (the ‘Wild Coast’), Dutch traders shipped almost 300,000 slaves to the Americas. This chapter discusses illness and health on board of the slave ships, and the development of medical care. Because of commercial, not humanitarian reasons the companies wished to bring the slaves as healthy as possible across the Atlantic. ‘Healthy’ is of course a very relative notion here: a death percentage of 15% was considered acceptable. Ironically, in order to stay below this percentage use of the medical knowledge obtained in the tropics and partly gotten from the Africans themselves was crucial. The implementation of this knowledge on the ships is discussed. A key figure in this chapter is the Swiss surgeon David Henry Gallandat, who went to West Africa on Dutch slavers in the 1750s. Gallandat was very keen on learning medical knowledge from the Africans themselves, visiting African cities and conversing with the African doctors. But he used the information in his tract on medical care on the slave ships.

Chapter 7

SURGEONS IN THE CARIBBEAN

At the same time, navy surgeons as Abraham Titsingh and Anton Schlapprizzi learned about prevention and treatment in the Dutch Caribbean. Titsingh learned from local inhabitants on Curacao and resented, as a ‘freeborn surgeon from Amsterdam’, the pretensions of academic doctors. Medicine to him was a matter of practice, not theory. Schlapprizi put this into effect when devising methods to deal with a new disease: the so-called ‘chocolate’ or ‘black flux’ (yellow fever) that plagued the crews on his ships.

Chapter 8

MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE BETWEEN BLACKS AND WHITES

The plantation economy of Suriname, in which the overwhelming majority of the population consisted of African slaves, became a ground of exchange of medical information between blacks, whites, and Indians. New diseases were brought to Suriname: not only epidemics of yellow fever and so forth, but also an increase in the prevalence of skin diseases such as leprosy and yaws. African healers were important in the treatment of slaves, but many whites sought as well solace with black herbalists and even sorcerers. Slaves were however reluctant to share their knowledge with white doctors and slave-masters. A few Europeans succeeded in creating bonds and exchanging knowledge with blacks: the naturalist and illustrator Maria Sybilla Merian, being a woman, succeeded in obtaining knowledge from her female slaves on plants, medicine, and abortifacients. The Scottish-Dutch mercenary John Gabriel Stedman when fighting the Maroons kept his health because of the information received of his black servant and of his black girl friends. One surgeon, Johan Carel Mangemeister, joined the Maroons and was executed after his capture by Dutch troops.

Chapter 9

THE WHITE ADVENTURER AND THE BLACK SORCERER

Sometimes local medicine made it into the pharmacopeia of European medicine and became an export product to Europe. This chapter details the career of quassiebita, a medicinal bark still used in Surinamese folk medicine. Already well known by the Indians of Guiana, information of the bark was given by the notorious African sorcerer Quassie to the Swedish adventurer Carl Dahlberg. Dahlberg successfully marketed the drug in Europe with the assistance of the famous Swedish botanist Linnaeus. Both Quassie and Dahlberg were figures on the fringe of their societies. Quassie was a feared sorcerer, a freed slave, and actually a collaborator of the Dutch in their war against the Maroons. Dahlberg was a typical adventurer, arriving penniless as a mercenary in Suriname and making his fortune there. It was the contact between fringes that made global circulation of knowledge possible.

Chapter 10

CONCLUSION: ADVENTURERS AND CIRCULATION OF KNOWLEDGE

In his book Against Method philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend based himself on the history of science to conclude that science does not progress through fixed methods. On the contrary, the history of science shows a kind of ‘anything goes’: what works in a given situation, works, and afterwards people will theorize about the why and how. Against the pretensions and power aspirations of so-called rationalists who extolled strict scientific methods, Feyerabend sketched an ‘anarchist’ or ‘dadaist’ theory of knowledge and advocated a complimentarity of methods.

The history of the 17th– and 18th-century ‘adventurer-scientists’ is an example of this kind of ‘anything goes’. Their search for knowledge was not theory-driven, but pragmatic and opportunistic. Pre-modern medicine with its flexibility of concepts and its emphasis on the local nature of knowledge and practices proved to provide a fruitful framework for this search. The Dutch Atlantic gave the social and political environment in which ‘adventurer-scientists’ could thrive, analogous to the buccaneers and freebooters of that period. As the buccaneers were ultimately used by the European powers to fight off the Spanish, the adventurer-scientists were ultimately used by the European powers to fight off disease and death. Without the ability of the adventurers to operate in hostile environments and contact other cultures, medicine in the tropics could not have developed.

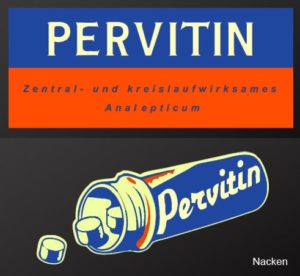

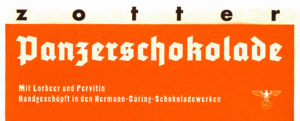

Deze week verscheen de Nederlandse vertaling van het boek van Norman Ohler over Drugs in het Derde Rijk.

Op verzoek van de uitgever heb ik hier een nawoord bij geschreven over het gebruik van Pervitin en andere drugs in Nederland tijdens de Duitse bezetting.

OVT voelde mij hierover dit weekend aan de tand.

De Duitse schrijver Norman Ohler heeft in het voetspoor van schrijvers en historici als Werner Pieper, Peter Steinkamp en als ik zo onbescheiden mag zijn mijzelf het drugsgebruik in Nazi-Duitsland verder uitgespit. Zijn boek Der totale Rausch werd in Duitsland een bestseller. In september zal een Nederlandse vertaling verschijnen bij uitgeverij Luiting-Sijthoff in Amsterdam. Op verzoek van de uitgever heb ik voor deze vertaling een nawoord geschreven, waarin ik de situatie rond drugs in Nederland onder de Duitse bezetting bespreek. (Zie ook mijn post op de Alcohol and Drugs History Society-website.)

THE ORIENTAL FRAMING OF DRUG ABUSE AND THE FEAR OF ‘GOING NATIVE’:

DRUG ADDICTS AND LEPROSY SUFFERERS IN THE AGE OF IMPERIALISM – A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

PAPER CONFERENCE ‘UNDER CONTROL – ALCOHOL AND DRUG REGULATION, PAST AND PRESENT’, LONDON 21-23 JUNE 2013

Stephen Snelders

1.

It is now the final paper and I guess everybody is longing for a well-deserved drink. I will therefore not delve into another detailed case study. On the contrary, after hearing all the interesting papers presented in our Addiction in Asia panels (and thanks to Jim Mills for organizing and stimulating these panels), I want to ask some questions about the relationship between addiction in Asia and the dynamics of drug control on a wider scale: I am interested here in the relationship between addiction in Asia and addiction in the Empires.

Much has been made by authors as Marianne Valverde and also by myself in the past of the relationship between the (negative) image of the drug addict and the rise of the nation-state in the 19th century. The drug abuser, who relinquishes control over his own will, is the exact antithesis of the responsible democratic citizen that is supposed to be the cornerstone of the democratic project. This analysis makes sense as far as it goes, but here I will suggest that we can also see something different and perhaps more fundamental if we take an imperial perspective. In this paper I will argue that it is not so much the rise of the liberal state that problematizes the use of drugs, but the fears that went together with the extension of imperial dominion over other races.

I will try to argue that our present-day framing of drug use cannot be understood without taking into account the imperialist and global context of 19th-century society. In fact, as I will argue, the process of the framing of drug abuse can be traced back to developments in 18th-century colonial society.

I will try to show this by making a comparison with another process of framing that took place at the onset of imperialism: that of the leprosy sufferer. You might be surprised to hear me make this connection, but is not a new one. In the 1960s, when a large drug-using culture expanded and prohibition became a contested issue, vocal proponents of this drug culture formulated the notion of drug users as victims of society, criminalized and stigmatized. Drug users were, in the sociological theory of Howard Becker, made into outsiders. Users compared themselves to the persecuted medieval witches and lepers. In his Histoire de la folie (Madness and Civilization, 1961). Foucault suggested that the stigma of lepers survived long after leprosy itself had become extinct in Europe and the leprosy asylums had emptied. ‘The values and images connected to the leprosy sufferer continued to exist.’ The games of exclusion were played again, but now with the insane. This analysis has been much discussed and debated. It is not my concern here to enter this discussion. I am not interested here in an exercise in Foucauldian discourse. I am interested however, in a much clearer connection: between the values and images around drug users on the one hand, and leprosy sufferers on the other, in the 19th century.

2.

There is a fascinating similarity in the cultural production of the images of the drug user and of the leprosy sufferer in the 19th century. In both cases, public and medical understanding of a problem mingles and confuses health and social issues, resulting in what I will call an oriental framing, a framing that is intimately bound up with the rise and development of imperialism. A comparison between the oriental framing of drug abuse and that of leprosy is enlightening in this respect. In making this comparison I will draw together the published literature on the histories of drugs and of leprosy.

To start with, we immediately perceive a similarity when reading this quote of leprosy historian Zachary Gussow. He made the important observation that a disease (or a disorder) in itself is perceived as socially threatening. when: ‘The condition must threaten a class of citizens, a way of life; it must arouse public concern; above all, it must give rise to action. It must become a social problem.’

The development of drug use as a social problem has been described and analyzed in the past. To memorize, David Courtwright has described the following development of the public image of drug users in the United States: in the second half of the 19th century the image of the user is still a far cry from our modern perception of the socially degraded junkie. The ‘dominant addict type’ in this period is a woman of middle age from the middle or higher classes. She is dependent on morphine or opium that she takes on the prescription of the family doctor. She looks rather like the typical housewife on barbiturates as depicted in the Rolling Stones’ Mother’s Little Helper.

According to Courtwright after around 1895 this image drastically changes. Drug use becomes more and more associated with non-medical use: at first smoked opium is seen as the most important drug of abuse. At the time of the First World War this has shifted to morphine, and by the 1930s to heroine. On the eve of the Second World War the ‘dominant addict type’ has changed into the ‘nonmedical addict’: the junkie who gets his drug in all possible ways. Next to opium cocaine, sniffed and not injected as in medical use, becomes the number two ‘diabolized’ drug. From 1900 onwards the image of the cocaine fiend develops, an image with strong racist overtones: the cocaine fiend in the South is often a black American sexually threatening white women. Needless to say, the development of the public image of the junkie goes hand in hand with increasing drug legislation. In the United States drug use becomes associated with deviant groups at the borders of society, groups with an often as inferior perceived biological make-up: Afro-Americans, Latin Americans, and so on.

3.

So far so good. But the cultural production of an Orientalized image of the drug abuser starts much earlier, in fact well before drug abuse came to be seen as a significant social problem, and well before the age of imperialism. Let’s get back to Thomas de Quincey and his Confessions of an English Opium Eater (1821) – maybe the earliest and certainly the most well-known example of the oriental framing. As Alethea Hayer wrote about De Quincey, whose Confessions of an opium-eater were first published in1821: he did not break any law, public opinion was not against him or even focused on him, and supplies of his drug were cheap and easily available. It was De Quincey himself who produced a cultural image of his drug use as a threat from oriental regions. In his 1991 study of De Quincey John Barrell claims that De Quincey was ‘terrorised by the fear of an unending and interlinked chains of infections from the east, which threatened to enter his system and to overthrow it, leaving him visibly and permanently ‘compromised’ and orientalised. The Orient here is actually an undifferentiated mixture of Chinese, Indian, Egyptian and other images, forming in the words of Barrell one ‘pathological identity’. ‘The Orient [for De Quincey] is the place of a malign, a luxuriant or virulent productivity, a breeding ground of images of the non-human, or of the no less terrifyingly half-human, which cannot be exterminated, except at the cost of exterminating one’s self, and which cannot be kept back beyond the various Maginot lines […] that De Quincey attempts to defend against the ‘horrid enemy’ from Asia.’ To quote De Quincey himself: ‘I was kissed, with cancerous kisses, by crocodiles; and laid, confounded with all unutterable slimy things, amongst reeds and Nilotic mud.’

As Alan Bewell points out in his Romanticism and Colonial Disease, this threat receives a powerful expression in De Quincey’s account of the Malay that one day knocks on his door. Not only is the Malay a fellow opium-eater and in this respect despite his cultural otherness similar to De Quincey himself, he is also a sexual threat to the white race, personified in his encounter with a beautiful young English girl who had never before seen anything Asian.

However, unlike the orientalized image suggest De Quincey himself was actually far from passive because of his opium use. On the contrary, he describes how, high on opium, he roams the streets of London on Saturday night, relishing the spectacles of the working classes enjoying their time-off. Only later in his life does he appear to succumb to the inactivity and torpor of the opium-eater. De Quincey himself was never an outcast of society.

His orlental framing of his drug use, with the associations of loss of self-control and of identity, confounded in a slimy pit, actually points as much to the past as to the future. It goes back to much earlier medical and social fears that prop up in the European colonial empires. The European who goes native loses the very core-essence of his whiteness and becomes a non-European itself. This is perceived as a a danger for European rule over other races in itself.

4.

As Bewell shows and as every student of early modern colonialism and colonial medicine immediately recognizes, the drug problem of De Quincey is not a national English, but an imperial problem. The changing disease-environment and the close proximity to slaves of African descent prompted inquiries in health and disease of the non-white population in the Caribbean as early as the 18th century. By the later eighteenth century the topic of what feminist historian Londa Schiebinger has called the ‘anatomy of difference’ between races was widely debated among the scientists and savants of Europe. Explanations for these ‘differences’ ranged between environmentalism and hereditarianism, including combinations of both. While in Europe this was of more theoretical concern, in the colonies the question of why and to what extent different races were prey to different diseases was of eminently practical concern. As Sean Quinian writes in his study of the French colonies, the ultimate distinction between the races was located in the amount of self-control a male European could exert, in order to regulate his functioning in accordance with the environment. ‘In a sense, the diseased body became the ultimate signifier of not just the pathological milieu but the total lack of physical self-control exercised by the European individual’, writes Quinian.

It is this racial stereotyping that in the 19th century gets transferred to the yellow and brown races of the Orient. De Quincey points the way. By 1870, the association between drugs, passivity, dirtiness, and race, is exemplified by Dickens in his unfinished The Mystery of Edward Drood. Interestingly enough, this is before the Age of Imperialism really gets into full swing. That drug use could be a habit of an active man, such as Alexandre Dumas’ Count of Monte Cristo, becomes a notion relegated to drug-using subcultures. Even Sherlock Holmes’ drug use is now a matter of medical concern. By the end of the 19th century, as Howard Padwa in his recent study Social Poison suggests, the association of opium use and Chinese is established as threatening the empire.

5.

As is the association with leprosy. The notion of leprosy as a perceived ‘danger to the empire’ is mostly associated with the end of the 19h century, the Age of Imperialism and the onset of scientific racism and Social Darwinism. At that time leprosy came to be regarded as an ‘imperial disease’ moving throughout the European colonial empires through migration of people and circulation of goods, and affecting white people in the process. In 1989 Zachary Gussow concluded in his study of American leprosy politics in an international context:

‘(…) by the nineteenth century [leprosy] had reappeared and by the end of the century had caused Western nations to panic. During the period of nineteenth-century imperialism, the disease was discovered to be hyperendemic in those parts of the world that western nations were annexing and colonizing. The discovery of leprosy in the colonial world, and the excitement in the 1860s generated by the announcement of an epidemic in Hawaii, revived Western concerns about a disease that otherwise remained but a memory.’

The ex-medical officer of the Confederacy, Joseph Jones, writes in 1887:

‘At the present day Louisiana is threatened with an influx of Chinese and Malays, with filth, rice and leprous diseases [,,,] patriots should contemplate with dread the overflew of their country by the unprincipled, vicious and leprous hordes of Africa.’

There are by 1893 355 Chinese sufferers in Louisiana, of which 300 in New Orleans. Leprosy, as opium use, seems to threaten the United States and in the 1880s measures are taken to prevent leprous Chinese coming into the country. What’s more, attention is again directed to white leprosy sufferers, who before 1880 seemed to have more or less been left in peace, and doctors go actively in search for the disease. In 1917 Congress decides on the creation of a national leprosarium to isolate the sufferers, not long after the passing of the Harrison Act against drug use. Other Anglophone countries as Australia and New Zealand, as well as Hawaii took their own measures against the Chinese immigrants from the 1880s onwards. The physician James Cantlie suggested in a 1897 report that all migrants should be examined, and sufferers expelled.

Gussow relates the ‘rediscovery’ and renewed fears of leprosy to anxieties about Chinese immigration and the endangerment of ‘American-ness’. But interestingly enough, similar processes were at work in China itself. Activists struggling for a more powerful China and the end of the ‘feudal’ Manchu dynasty had casted opium use as a vicious habit brought in by the western barbarians to undermine the celestial empire (an interpretation that is rejected by Dikötter et al in their history of Chinese drug culture). In China the anti-opium offensive connected to the Opium Wars and later were related to the rise of bourgeoisie and nationalism. Opium poisoned the nation, especially after the lost war against Japan of 1895. In a similar vein, to Chinese nationalists and the revolutionaries of 1912 leprosy became a sign of the undisciplined body, a matter of shame for China, necessitating isolation of sufferers and public health policies.

6.

Conclusion

The framing of drug abuse and leprosy as socially threatening diseases was not solely a matter of local developments. Imperialism meant the need for more control of geoographical territories as well as of global migration movements. Racial framing, connecting the diseases with yellow and black ‘inferior races’ was a central part of the process of understanding both conditions, but also of stigmatizing drug users and leprosy sufferers. Where around 1800 one could take his drugs rather publicly, or mingle as leprosy sufferer in most regions around the globe with other people, by 1900 this had become impossible and suspect. The opium user of 1900 was no longer the active Count of Monte Cristo, taking a rest on his way from one part of Europe to another, or De Quincey touring the streets of London in psycho-geographical research, but the languid and passive degenerate of the London opium shed.

Of course, different nations had different timing and styling of these developments. Can we understand these differentiations better by taking a look at the imperial contexts?