THE BLUE LOTUS REVISITED: PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS OF DRUG USE IN THE DUTCH EMPIRE, c. 1900 – 1942

Stephen Snelders & Toine Pieters

Paper Drugs and drink in Asia: New perspectives from History

June 22-24, 2012, Shanghai University, China

Introduction

The Dutch colonial empire was in the first half of the 20th century one of the most important manufacturers and distributors of psychoactive drugs, as is well known: of smoked opium in the Dutch East Indies, and of coca and cocaine on a worldwide scale. Dutch drug policies of that period, in the colonies, in the Netherlands themselves, and in international organizations and negotiations, had to balance between a number of factors and (seemingly contradictory) motives: economic motives, ethical concerns about the harmful effects of drug use, and political demands to adjust to international drug regulation regimes. Historians have studied all of these factors up to a certain degree. Little is known about another important factor: perceptions and sentiments concerning drug use, including drug policies, production and trade, among the public both in the Netherlands and in the Dutch colonies.

How did the inhabitants of the Dutch colonial empire, from various social classes and cultures (Dutch, Malaysian, Chinese, Dayak etc.) perceive and feel about the use of different drugs? To what extent was it seen as problematic? Did perceptions and sentiments change in the interwar period up to the Japanese invasion of the East Indies? And how did public opinions influence policies in the homeland as well as in the colonies?

Looked upon from a bird’s eye view, the Dutch empire in the interwar period shows many contradictions in its national and colonial drug policies. If we follow the most authoritative and extensively researched study on drug policies in the home land, we notice that from the Shanghai conference of 1909 onwards the Netherlands follow (albeit sometimes hesitantly and unwillingly) the lead of the United States and the League of Nations in constructing and implementing a regime of increasing prohibition of production, distribution and possession of drugs. This in spite of the non-existence until after the Second World War of a drug problem in the Netherlands itself. How is this rather docile position of Dutch governments, continuing until the 1970s, to be explained from the perspective of internal politics? At the same time policies in the Dutch colonial territories in the East Indies were remarkably divergent. Where in the home country strict policies were enforced against uses of opiates and cocaine, opium was imported in the Dutch East Indies by the colonial states, refined to smoked opium in a state factory, and distributed to the subjugated population using a system that was a remarkable predecessor of the famous ‘coffee-shop’ policies of the past 35 years. At the same time coca became a successful agricultural crop exported to Europe, in particular Germany and the Netherlands itself, for the legal production of (medicinal) cocaine. How are these paradoxes to be explained? And how at the time did Dutch citizens perceive these paradoxes – if they were perceived at all?

One way of finding out more about these perceptions is by an analysis of newspapers. We are of course very aware that these do not necessarily represent the perceptions, opinions and sentiments of every segment of the Dutch public or of non-conformist individuals, and are as much aware that public opinion is only one among many factors influencing the construction and implementation of drug policies. Nonetheless, an analysis of the daily press in the different parts of the Dutch empire gives us some insight into the dynamics and development of public opinion. Were drug policies in the metropolis as well as in the colonies uncritically accepted in the whole range of the daily press? Or can we detect critical voices? When, to what extent, how and why was drug use seen as a major problem? Was it seen as a problem of individual citizens, of public health and/or of public order and crime control? Were differentiations made among drug users respective of class, gender or cultural and ethnic background? And what is maybe the most interesting question: was there any perception of the paradox of both prohibiting drugs and making money by selling them?

This paper will present preliminary results of a project of historical text mining of a digitalized data set of millions of pages from Dutch and Dutch-Indonesian newspapers from the period, using semi-automatic tools. In the following sections we will explore more in depth our research problematic, our research method, and our (preliminary) findings. We will start with some hypotheses about what we will expect to find.

- The problem of drugs in the interwar period

One of the essential problems in the terrain of drug history to explain in all its diversity is the continuous increase of drug prohibition since the beginning of the 20th century, coinciding with an increasing ‘diabolisation’ of the drugs and their uses.

Let us summarize some findings of drug historians on the period just before the ‘starting point’ of our research in time: the fin-de-siècle of 1900. The problem of drug control is moving up the public agenda then, within two seemingly different contexts. One is a trend to increasing democratization, individualization, secularization; the other is a trend to empire building. To start with the first one: democratic and liberal ideologies are based on the assumption of the existence of a rational and free citizen. But this assumption is threatened by drug dependence. Marian Valverde has therefore described drug addiction as the liberal disease par excellence. It is a disease of the will. The willpower of the addict is his or her only tool in getting rid of his or her dependence on drugs: in freeing him or her from his slavery. The drug addict is enslaved to a substance = therefore not rational = is therefore not the ideal emancipated citizen. In a society in which the participation and involvement of the citizen is becoming more and more important, drug abuse and dependence therefore threaten not only the individual citizen, but society itself – at least in the view of many politicians, social reformers, doctors and scientists.

From this perspective the campaign to introduce an international regime of drug control and prohibition, led by the United States and China, can be expected to have gained some support in the Netherlands. In Dutch there is a semantic support for this perspective. The Dutch word for addiction, verslaving, is related to slavernij or slavery. Slavery in the strictest sense was abolished in the Dutch colonial empire only as late as 1863 – the same year as in the United States. But the new slavery to drugs took time to develop. It is therefore interesting that the word verslaving was not yet used for drug dependence before the Second World War.

A second context of drug control was empire building. Since the days of the East India Company the sale and distribution of opium in the Dutch controlled territories in the East Indies had been an important source of revenue. Between 1894 and 1914 a new system was gradually introduced in the Dutch East Indies: Opiumregie (‘opium direction’). This was a further extension of the opium monopoly of the Dutch colonial government. Not only the import of opium was now a monopoly of the colonial state, the production of smoked opium (the end-product for the user) became a monopoly of the Dutch state-factory, and the distribution was organized through a system of concessions, in which there were differentiations made in the availability of the drug in particular regions and for particular population groups. In this way, the Dutch government hoped to increase profits, to exclude the Chinese intermediate traders who had until then bought the rights for the distribution of the drug, and to facilitate the fight against opium smugglers, since the new standard product of the state factory was easily discernible from illegal products. However, the arguments for introduction of the Opiumregie were not limited to economic reasons or public security issues. The Dutch government actually claimed that increased control of the whole chain of opium import, production and distribution would lead to a reduction of opium abuse and dependence among the subject populations, who would have less reason and opportunity to turn to non-controlled substances and whose use level could be rigidly controlled.

It is therefore unsurprising that on the conference in Shanghai in 1909, the Dutch delegation was far from enthusiastic about the American proposal to label the non-medical use of opium as immoral. On the other hand, the Dutch delegate’s own proposal to label a state monopoly as in the Dutch East Indies as the most effective method of opium control gained little support. In a way that can be regarded as typical for Dutch politics, the Netherlands moved along with the international trend to prohibition, without changing its actual policies in the colonies. The Netherlands hosted the The Hague conference resulting in the First International Opium Treaty of 1912; they ratified the treaty in 1915; and in 1919, after the American victory in the First World War, the Dutch parliament accepted the first opium law prohibiting the production and distribution of opiates and cocaine. The law became in force in 1920 and is still the basis of Dutch drug policies. In 1928 personal possession of opiates and cocaine was made illegal as well. In the East Indies however the colonial government let the system of Opiumregie remain intact until the occupation by the Japanese in 1942.

Within this political and legal context it is to be expected that the position of being a user changed drastically. The nature and pace of these changes remain complex and differentiated between countries, cultures and classes. A hundred years before, dependence on opium was a known phenomenon, but the dependent user was not yet seen as a criminal. As Alethea Hayer wrote about Thomas de Quincey, whose Confessions of an opium-eater were first published in1821, De Quincey did not break any law, public opinion was not against him or even focused on him, supplies of his drug were cheap and easily available, and the dangers of opium use not well understood. A century later the Dutch opiate or cocaine user is not only in danger of alienating himself from society, at an even more basic level it becomes hard for him to get a supply of his drug. Images and perceptions of drugs and drug use have changed. But in the Netherlands this is independent from the actual existence of a drug problem: the problem drug is not opium, heroine, morphine or cocaine, but alcohol. Legislation and the implementation of a law enforcement regime seem to come before, not after the appearance of the drug problem. As Paul Gootenberg writes: ‘What are not very convincing are attempts to see the progression of drug policy history as a Whiggish reform – that is, the notion that drugs were successfully banned when science awoke to their medical or social dangers.’ But if there was no real drug problem we must ask: were perceptions and sentiments changing among the public before the drug problem actually came into existence, thereby creating a support base for participation in the international trend towards prohibition and control?

How did developments in the Netherlands fit into what we know about other countries? Since the 1970s the Netherlands have an international reputation for tolerant drug policies, though in recent years there has been a conservative backlash. In a way, this backlash picks up again where the Netherlands stood before the 1970s. Prohibition and law enforcement were up till then central to Dutch policies, at least since the introduction of the Opium law in 1920. However, when we look closer at the interwar period the Netherlands can more easily be fitted into a British or German model, than in an American. Whereas drug policies in the United States for an important part were directed at the prosecution of individual drug use as well as drug traffic, in European countries as Great Britain, Germany and the Netherlands users were mostly left alone and policies were primarily directed at health care: regulating doctor’s prescriptions, the market for pharmaceutical products, and addiction care. As said in the Netherlands there were hardly any problem groups and the illegal trade was for the most part transit trade through the Dutch harbours into other countries. This does not answer our questions though: why did the Netherlands follow international regulation trends if there was no drug problem, and how did this relate to the different drug policies in the Dutch colonies in the East Indies?

- Public images: Constructing drug users

Despite the lack of a drug problem, historian Marcel de Kort gives some evidence that the public image of drug users became more and more negative since the second half of the 19th century. What he did not do was to make a more systematic study and analysis of the development of this image. It is here that we move in and try to follow-up on De Kort’s studies by making this analysis, and to start with we are taking a closer look at the daily press.

Where in the newspapers do we have to look for perceptions, opinions and sentiments of drug use and drug users? Leading articles and opinion articles about the drugs themselves or specific policy measures are an obvious first choice. But our search will not be limited to this obvious choice. Public debates are one arena where perceptions etc. are constructed and structured, but it is not the only one and, if we take a more Foucauldian perspective, not the most important or decisive one. Implicit assumptions and perceptions around drugs are pervasive throughout our culture, and to be found in detective stories, advertisements, visual representations and journalistic reports of many kinds. Implicit assumptions are so much more powerful on the imagination, exactly because they are ‘given’ and not to discussed. For the uninformed or biased readers these hidden discourses construct and reinforce a whole range of associations with drug use, for example as dangerous, criminal, and shady, or as having distinctly unpleasant results. There is no nuance or discussion in hidden discourses and for this reason they can have a powerful impression upon a reader, who doesn’t know anything about the issue at first hand. If such perceptions occur again and occur in for instance popular culture, it is an important indication for public opinion.

To us, these ‘implicit’ or ‘hidden’ discourses are to be found and analysed as much as the more explicit open debates. Digital tools give us better possibilities to find these hidden discourses than more traditional methods, as we will see later in this paper. They will help us in getting a picture of the public images of the drug and of the drug user.

In our research we try to find evidence for or against the kind of dynamics that historians have constructed for other countries than the Netherlands. For the United States David Courtwright concluded the following development of the public image of drug users: in the second half of the 19th century the image of the user is still a far cry from our modern perception of the socially degraded junkie. The ‘dominant addict type’ in this period is a woman of middle age from the middle or higher classes. She is dependent on morphine or opium that she takes on the prescription of the family doctor. She looks rather like the typical housewife on barbiturates as depicted in the Rolling Stones’ Mother’s Little Helper.

According to Courtwright after around 1895 this image drastically changes. Drug use becomes more and more associated with non-medical use: at first smoked opium is seen as the most important drug of abuse. At the time of the First World War this has shifted to morphine, and by the 1930s to heroine. On the eve of the Second World War the ‘dominant addict type’ has changed into the ‘nonmedical addict’: the junkie who gets his drug in all possible ways. Next to opium cocaine, sniffed and not injected as in medical use, becomes the number two ‘diabolized’ drug. From 1900 onwards the image of the cocaine fiend develops, an image with strong racist overtones.

Needless to say, the development of the public image of the junkie goes hand in hand with increasing drug legislation. In the United States drug use becomes associated with deviant groups at the borders of society, groups with an often as inferior perceived biological make-up: Afro-Americans, Latin Americans, and so on.

Can we detect in European societies such as the Netherlands and in their colonial empires a similar dynamics in the construction of the public image of the drug user, or are there differences, analogous to the differences in drug policies? Is the emphasis in the Netherlands more on medical aspects of his behaviour as dependence and addiction, or on social aspects as criminal and other deviant activities? Recent historical research suggests that in neighbour country Germany criminalization and negative judgments of drug users were in the period 1880-1940 not as strong as in the United States. Even in the Third Reich, where we definitely would expect something different, there was no systematic persecution of drug users, while alcoholism could lead to detention in a concentration camp or forced sterilization. Maybe this recent research gives a too rosy picture of the situation of German drug users. A Berlin commissar of the criminal police (Kripo) wrote in 1935 that there hardly was any drug use under the Nazi government, but explained at the same time that there should be published as little as possible about this use to prevent seductive examples. Still there could have been a relation with the perspective of German doctors, who following the pioneering study of Eduard Lewinstein from 1883 did not categorize drug users as mental or biological degenerates (unlike alcoholics). In the Netherlands the work of Lewinstein was regarded as exemplary.

- The Chinese Connection: xenophobia, fears and drugs

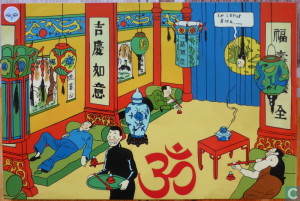

Nonetheless, by the time of the Second World War there are negative images of drug users to be detected in Dutch public media, especially if we look at the ‘hidden discourses’ we mentioned above. A good example is Dick Bos, a popular pulp comic series. The first five parts were published in instalments in weekly papers in the years 1940-1942. Dick Bos is a detective who is an expert in an Asian fighting art (jiu jutsu). In his first appearance he is immediately caught up in a drug case. Bos gets on the trail of a gang smuggling cocaine on a Chinese ship. When the gang captures him he is send to China and put to work as slave on a plantation. Of course he escapes and ultimately helps to capture the gang.

That the actual relationship between cocaine and China was a little more complicated does not matter here: many (young) readers of the comic would have become firmly convinced of the connection. In the follow-up story Bos again battles with a gang of drug smugglers, in this case dealing in opium. In part 12, ‘De blauwe diamant’ (The Blue Diamond) cocaine is again of central importance. The gang dealing the drug recruits its clients through the wife of a psychiatrist who needs the money. She peddles the drug among the patients of her husband.

In Dick Bos opium and cocaine are clearly and visual associated with a dark underworld, low-life taverns, unreliable Chinese, and harbours. At the same time the drug trade reaches into the most respectable circles. It is interesting that users are never cool, in the way Sherlock Holmes could be depicted as an addict but still cool. They are psychiatric patients and clubbers that compare poorly to the sober Dutch hero Dick Bos.

But why is there an emphasis on the Chinese connections? Did writer Alfred Mazure only follow American examples (Dick Tracy etc.)? Although these influence were important, the Chinese connection shows how the construction of images of drugs was closely related to global development in the Dutch empire that ruled over Chinese population groups in present-day Indonesia, Suriname… and the Netherlands itself.

From the first arrival of Chinese immigrants in the Netherlands shortly before the First World War they were surrounded with negative images. Part of this had to do with the fact that the first generation was imported by the big Dutch steamship companies in 1911 to work as sailors, mostly as stokers. In this way the companies tried to break the power of the trade unions. This did not make the Chinese popular among the Dutch labour class. In 1927 around 3,000 Chinese were employed on the Dutch transport and mercantile fleet. In the towns of Amsterdam and Rotterdam small ‘China towns’ came into existence. The studies of De Kort and others have shown how the Dutch police and other authorities from the 1920s onwards produced images associating these China towns with drug use, gangs and criminal behaviour. The steamships on which the Chinese worked were seen as an important means of transport for drugs smuggling rings.

5. The Chinese connection in the daily press

To what extent are the images and associations around drugs and drug users in Dick Bos representative for perceptions, opinions and sentiments among the general public in the interwar period? Is there anything characteristically Dutch about these images? Do we find these images before the start of drug legislation in 1920, or even before 1909, the year of the Shanghai conference? In short, when make Chinese opium gangs or addicted nervous patients their appearance in the Dutch public imagination?

We are researching this question by using the data in the Historische Kranten (Historical Newspapers) database of the Royal Library of the Netherlands in The Hague. The aim of this database, that is freely accessible to users through the Internet, is to give a representative selection of digitalized newspapers from all parts of the Dutch empire since 1618. Digitalization is still in process, but in the course of this year the database should contain around nine million pages of newspapers. By doing full-text searches researchers can dispend with more traditional ways of doing newspaper research, such as sample or backbone studies. To us, this is of special importance since we attempt to find the ‘hidden discourses’ next to the explicit discourses and debates that are easier to find with traditional methods ‘by hand’.

To facilitate complex searches and analysis including text mining and sentiment mining we are currently using a web application that we are developing at the Descartes Centre for the History and Philosophy of the Sciences and the Humanities at Utrecht University, in collaboration with the Department of Computer Sciences at the University of Amsterdam (Fons Laan and Daan Odijk): WAHSP (Web Application for Historical Sentiment mining in Public media). This application should become available as an open-source program. Though the development is still in its infancy we can use it to make quantitative analyses as an added tool to the more qualitative analyses of individual documents, of the kind that we did with the Dick Bos comics and other sources. In this way we can make evaluations of the extent to which images as in Dick Bos were representative for the interwar period, or be attended to the existence of images we would not have expected.

We can give here some examples of our preliminary findings, with the caveat that both the Historische Kranten database and the WAHSP application are still uncompleted when writing this paper. We take a look at associations with the drugs that were the target of the Opium Law of 1919: opium, morphine, heroine and cocaine. We will split these associations in four time periods: (I) before the The Hague conference of 1912; (II) from 1912 to the enforcement of the Opium Law in 1920; (III) between 1920 and 1928 when the law was changed making possession an offense; (IV) and from 1928 until the Second World War, when people presumably had other things to worry about.

What is significant is that after 1920 the associations around drugs seem to change. The generic term drugs, which in present-day Dutch is in general use to describe illicit recreational drugs (but not pharmaceutical drugs in medical use), did not exist yet in the Dutch language of the interwar period. The terms used were narcotica, or verdovende or verdoovende middelen (all meaning ‘narcotics’). Before 1920 most uses of these words in the newspapers referred to opium or to chloroform, that had an important role as a narcotic in medicine. But the number of articles dealing with these narcotics is very limited compared to the periods 1920-1928 and 1928-1940. After 1920 the number multiplies with a factor 16. The associations change as well: from ‘medicines’, ‘poisons’, ‘science’, ‘pharmacies’, ‘sleep’ or ‘narcosis’ to ‘police’, ‘contraband trade’, ‘arrested’, ‘confiscated’.

Not only are there increasing associations of the generic term with crime, the same holds for the individual drugs: opium, morphine, heroine, and cocaine. And significantly opium is very much associated with Chinese, China, or with the Dutch East Indies. Even ‘Opiumregie’, the opium distribution and control regime of the colonial state in the Dutch East Indies, is in the first place associated with Chinese (and pathetic) users, and with Chinese crime syndicates that try to evade the Opiumregie by smuggling illicit opiates into the East Indies: smoked opium of a different quality than the standard government issue, and in the 1930s morphine and heroine. Though the number of users stagnates, the need for something stronger seems to be growing.

Apart from the Chinese connection there are some problems with indigenous users in the Netherlands itself. The story line from The Blue Diamond, in which Dick Bos exposed the wife of the psychiatrist as an accomplice of cocaine dealers, turns out to be based on a real life newspaper story. But in a general comparison, the problems with Dutch users are extremely limited. Illicit trade is, as earlier studies had already concluded, in the first place transit trade through the Dutch harbours into other countries.

6. Conclusion

As a preliminary conclusion our analyses place the construction of a drug problem in the Netherlands in the period after the introduction of the prohibitive Opium Law, and connect it clearly not as since the 1960s with a youth problem, but with China and the Chinese. The drug problem is then a problem of empire, or rather: it is not a problem of empire, because since most users are expected to be Chinese or at least non-Dutch, their use could be tolerated or controlled with an Opiumregie, and stricter policies on the American model were unnecessary in the eyes of public opinion.